- Dyed textiles

- Tokyo

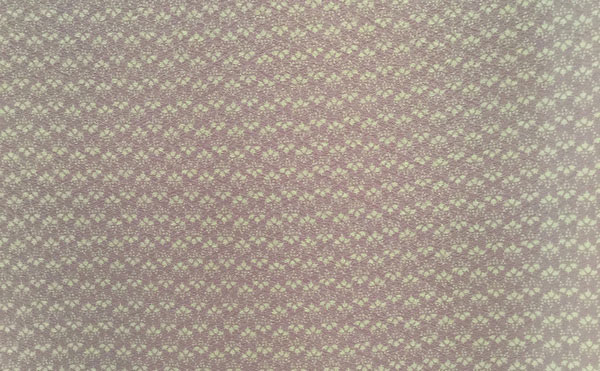

Tokyo fine-patterned dyeing Tokyo some komon

Delicate and traditional beauty dyed by hand

that reflects the skills of the artisans

Description

What is Tokyo fine-patterned dyeing ?

Tokyo fine-patterned dyeing (called Tokyo some komon in Japanese) is a stencil dyed textile produced in different wards of Tokyo like Shinjuku and Setagaya. It was designated as a traditional national craft in 1976.

This textile can seem plain from afar, however, when examined up-close there are delicate geometric designs. Komon means fine patterning and two types of this craft are Edo komon and Tokyo oshare komon. The former uses monochromatic, fine patterns, while the latter has much larger, multicolored designs, but both use handmade Japanese paper as a stencil when dyeing.

The main patterns of this craft include same komon (shark pattern as it looks like fish scales), kakudoshi komon (grid pattern), gyogi komon (diagonal line pattern) and gokusame komon (finer version of same komon). In general, the quality of the product is higher when the pattern is finer.

This craft is a type of stencil dyeing that uses backing paper made through pasting together several sheets of traditional Japanese paper. An experienced carver meticulously cuts a pattern into the backing paper. Then, the process of handcoating starch on the textile is done by a dye artist.

History

Komongata zome is a stencil dyeing technique that has existed since the Muromachi period (1338-1573) but became popular in the early Edo period (1603-1868) when samurai started to use it for ceremonial dress.

Feudal lords called daimyo had their castles in Edo (now Tokyo) and each clan had a personal pattern. Therefore, the demand for this craft increased and the designs used for the lords' clans became traditional patterns of the craft. Although initially only feudal lords wore Tokyo fine-patterns, commoners started wearing this craft midway through the Edo period and a wider variety of chic patterns developed, including designs with animals, plants, seven gods of good fortune, or treasure patterns. As more variations of designs became available, the demand for Tokyo fine-patterned dyeing increased.

A law enacted at the beginning of the Meiji period (1868-1912) required samurai to cut their topknot. This was followed by a rapid change to Western dress and a significant decline in men wearing Tokyo fine-patterned kimono. However, the amount of women wearing fine-patterned kimono also increased.

General Production Process

- 1. Carving of the pattern

Two or three sheets of handmade Japanese paper are pasted together using persimmon tannin to make stiff tracing paper into which stencil designs are cut. The carvers use the tools they have made like a small knife, gimlet, or chisel, and cut fine patterns in the stencil paper. Those that express very fine designs are called goku where at least 900-1000 holes are engraved within a three centimeter (approximately one inch) square.

Different cutting styles include pushing the blade through the paper, engraving with a gimlet, using an oval blade and drawing the blade towards the carver.

- 2. Adjustment of starch with dye

The base color and pattern color are the two most important factors for dyeing quality. First, a paste is made by mixing a small amount of salt into glutinous rice flour and rice bran, which is steamed to make the base starch into which the dye is mixed. Artisans repeat trial dyeing many times to get the right composition. If chemical dyes are used, adjusting the color is a little easier as it is more uniform, an experienced craftsman’s skill and intuition is still required.

- 3. Starching and dyeing

Starch is applied to the textile in preparation for dyeing.

First, a white silk textile is stretched tightly on a board about seven meters long (about twenty-three feet long). The stencil pattern is placed on top of the textile and masking starch is applied to the textile using a spatula made of Japanese cypress. Starch is applied through the stencil and sections with no starch are dyed. Artisans say that applying starch evenly on a roll of textile that is about twelve meters long without moving the stencil at all is the most difficult process in the production of this craft. In addition, the dots at the edge of the pattern where the patterns are joined must match. However, traditional Japanese paper tends to become dry, so it must be dipped in water before joining the patterns.

- 4. Drying the textile on a wooden board

When the starching and dyeing is complete, the next process is to dry the starch while the textile is still stretched on the wooden board. If the design requires multiple colors, the design becomes brighter by dyeing and starching over again, multiple times.

- 5. Dyeing the base color

When the starch is dry, the textile is removed from the board for dyeing the base color. Starch with dye is applied all over the textile using a large spatula before the fabric is put into a shigoki machine, which rotates and pulls the textile to ensure good absorption of the base color.

- 6. Steaming

The textile is put in a steam room before it becomes too dry and steamed at about 90-100℃ (about 194-212℉) for 15-30 minutes. Steaming fixes the dye in the starch, but skilled temperature control is required. The artisan controlling the temperature must be experienced enough, for example, to be able to sense a subtle change in the fermenting starch's scent.

- 7. Washing in water

The steamed cloth is put in a water tank to soften the starch and carefully wash out excess dye and starch. Historically, fabrics were washed in rivers so dyeing workshops would congregate along a river with a good flow of water suitable for washing textiles, such as the Kanda River.

- 8. Drying and finishing

The piece is dried in the sun and the width of the textile stretched by steam ironing. Then the textile is inspected for the evenness of fabric and any mismatches in the pattern are corrected with a brush and dye. After these finishing touches, the textile is complete.

Where to Buy & More Information

Tokyo Somemonogatari Museum

-

Address

-

Tel.+81-3-3987-0701

-

ClosedSaturdays, Sundays, national holidays

-

Business HoursMonday to Friday 10am to noon 1pm to 4pm

-

Website

See more Dyed textiles

- Kaga textiles

- Kyo textiles

- Tokyo fine-patterned dyeing

- Nagoya textiles

- Kyo-komon textiles

- Arimatsu tie-dyeing

- Ryukyu traditional textiles

- Tokyo textiles

- Kyo dyed textiles

- Nagoya kimono-dyeing

- Kyo kimono-dyeing

- Naniwa Honzome Hand Dyeing

- Tokyo Honzome Chusen

- Tokyo Plain Dyeing

See items made in Tokyo

- Edo kiriko cut glass

- Edo wood joinery

- Edo glass

- Murayama-oshima tsumugi silk

- Tokyo silverware

- Edo patterned paper

- Tokyo fine-patterned dyeing

- Edo bamboo fishing rods

- Tama brocade

- Hachio island silk

- Woodblock prints

- Tokyo textiles

- Edo-sekku doll

- Edo Hyogu (Art Mountings)

- Edo Oshi-e Pictures on Embossed Fabric

- Edo tortoise shell crafts

- Tokyo Honzome Chusen

- Tokyo Koto (Japanese Harp)

- Tokyo Plain Dyeing

- Tokyo Shamisen

- Tokyo antimony craft