- Household Buddhist altars

- Aichi

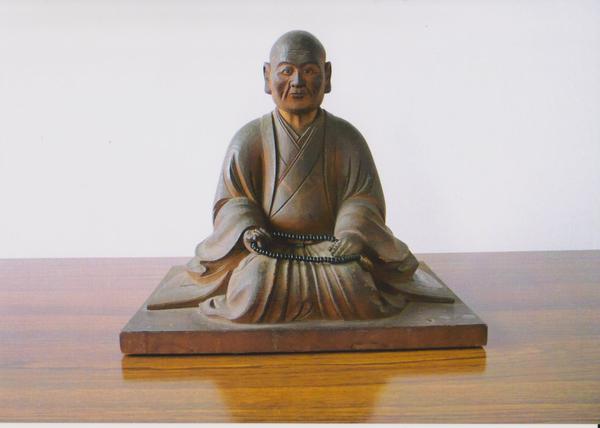

Owari Buddhist altar equipment Owari butsugu

Beautiful amber tortoise shell

transformed by the art of water and fire

Description

What is Owari Buddhist altar equipment ?

Owari Buddhist altar equipment is made in Nagoya and neighboring cities in Aichi prefecture called the Owari suburbs. Owari Buddhist altar equipment was first founded as a religious craft by the missionaries of the forefather of the Jodo-shinshu sect's restoration, Rennyo. A canal was built around Nagoya castle which made it easier to procure the material wood such as Japanese cypress and other goods. This favorable environment for making crafts was the foundation of Owari Buddhist altar equipment. Lacquered wood crafts were the most popular but many other articles of different shapes and utilities were created. They specialized in producing various articles for all Buddhist sects for both temples and households, and provided many high-quality products all around Japan. Wood blocks and round table boards used in today's Buddhist temples around Japan are only produced in the Owari suburbs. There are several unique techniques used to produce this craft such as applying heavy pressure to gold leaves or axis-bending wood. Other than Buddhist altar equipment, different articles for festivals and other rituals are also produced.

History

In the end of the Edo period (1603-1868), lower-class samurai made crafts as a side business. The techniques they developed from these jobs were used to create Buddhist altar equipment. During the Meiji period (1868-1912), the high quality of Buddhist altar articles made in Nagoya using Kiso cypress (Japanese cypress) wood had made them so popular that they began selling them all around Japan. Even the regions known for producing Buddhist altar articles, started to order more from Nagoya. Nagoya became a major production area for Buddhist altars and their equipment at the beginning of the Showa period (1926-1989). The products were even exported to Taiwan, Korea, Manchuria (north eastern China) and Sakhalin. There had over 630 ateliers in the Owari suburbs and more than 1700 employees. Many shrines and Buddhist altars were destroyed by the air raids during World War II. However, thanks to a great effort of reconstruction right after the end of the war, Buddhist altar equipment construction was back on its track by 1950 and soon spread all over the country. In 2014, the association to preserve Owari Buddhist altar equipment was inaugurated. In 2017, Owari Buddhist altar equipment was designated as a Traditional craft by the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry.

General Production Process

- 1. Creating the wooden base Different dry wood such as pine, cypress, zelkova or camphor tree are used to prepare the wooden base. Each step and every part of the equipment requires special tools.

- 2. Carving Several types of chisels and knives are used for carving. High-skilled artisans use their many years of experience to finely carve the traditional designs.

- 3. Base coating Polishing powder or powdered calcium carbonate mixed with animal glue or raw lacquer is used as the base coating. It is applied to the wooden base and dried. This base serves several important purposes. It will help fixing and bringing out the colors as well as assuring a smooth and soft finish to the lacquer.

- 4. Lacquering Special brushes and spatulas are used for applying lacquer. It is then dried out in a type of drying room where the humidity is controlled. There are many techniques to apply the lacquer and each have a different finish.

- 5. Applying the colors The patterns are painted with colors. Powdered calcium carbonate is sometimes used to give a three dimensional effect to the design. There are various techniques; painted directly on the wooden base, painting on the base coating and painting on the gold leaf.

- 6. Creating metal ornaments Arabesques or Buddhist flower designs are carved on copper or brass metal sheets with a chisel. In the spaces left uncarved, little round spots called nanako are pushed into the metal. Carving techniques such as hairline engraving, beating and ground carving are used.

- 7. Adding the gold leaves A coat of lacquer is first given to places where gold leaves are to be applied. A cloth is used to wipe and even the lacquer, and the gold leaves are applied. After some time, floss silk is used to press and settle the gold leaves. The gloss can be adjusted by the number of times the leaves are wiped.

- 8. Maki-e The base design is drawn on Japanese traditional paper, traced with red iron oxide lacquer and reproduced on the spot where the Maki-e is to be applied. Lacquer is then applied to this spot and different kinds of gold powder are sprinkled on top of it. After letting it dry in the drying room, the finished gold lacquer is sometimes wet sanded with charcoal, rubbed with lacquer and polished again.

See more Household Buddhist altars

- Osaka Buddhist altar

- Hikone Buddhist altar

- Iiyama Buddhist altar

- Nagoya Buddhist altar

- Kanazawa Buddhist altar

- Kawanabe Buddhist altar

- Kyo Buddhist altar

- Hiroshima Buddhist altar

- Mikawa Buddhist altar

- Kyo Buddhist altar equipment

- Nanao Buddhist altar

- Yamagata Buddhist altar

- Yame-fukushima Buddhist altar

- Nagaoka Buddhist altar

- Sanjo Buddhist altar

- Niigata-shirone Buddhist altar

- Owari Buddhist altar equipment

See items made in Aichi

- Tokoname ware

- Akazu ware

- Toyohashi brushes

- Nagoya textiles

- Nagoya Buddhist altar

- Owari Cloisonné

- Arimatsu tie-dyeing

- Mikawa Buddhist altar

- Seto-sometsuke ware

- Nagoya kimono-dyeing

- Nagoya traditional paulownia chest

- Okazaki stonemasonry

- Nagoya Sekku Kazari

- Owari Buddhist altar equipment

- Sanshu Onigawara Crafts