Photo:Takuminote - MASTER'S ARTISTRY – production team

Photo:Takuminote - MASTER'S ARTISTRY – production team

- Metal works

- Niigata

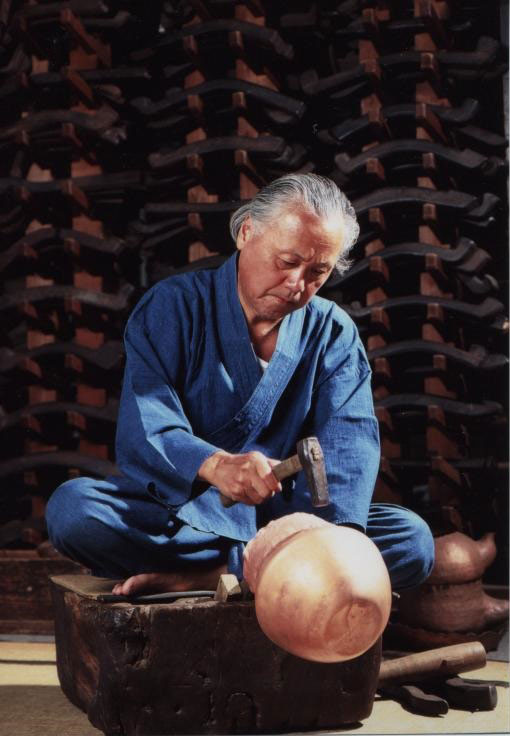

Tsubame-tsuiki copperware Tsubame tsuiki doki

Scintillating light and simple daily utensils

Beauty of form hammered from a single piece of copper

Description

What is Tsubame-tsuiki copperware ?

Tsubame-tsuiki Copperware (called Tsubame Tsuiki Douki in Japanese) is a type of metalware made on the outskirts of Tsubame, Niigata prefecture. Since the middle of the Edo period (1603-1868), kettles and other crafts have been produced from copper extracted from nearby Mount Yahiko. A malleable copper plate is hammered by hand, a technique that the name tsuiki refers to, using a range of traditional skills and method. This technique gives a shiny appearance to Tsubame-tsuiki Copperware and the texture of the copper ages well with long-term use and proper care. Each product is hammered several hundred thousand times, which makes the surface have a smooth porcelain-like look. Various products are made for everyday use such as vases, water pitchers, and teapots as well other artistic work. It is said that copper teapots are ideal for pouring tea as the taste becomes milder due to metal ion reaction. Tsubame-tsuiki Copperware was designated as a traditional craft by the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry in 1981.

History

Tsubame in Niigata prefecture, has been famous for metalwork production since the early Edo period, when Japanese iron nails used for building construction were made. Tsubame-tsuiki Copperware originates with artisans who were visiting the area from Sendai, Miyagi prefecture during the middle of the Edo period and introduced the tsuiki, hammering techniques that had been preserved for over two hundred years. However, Tsubame is currently the only area in Japan still producing copperware with this technique. High-grade copper extracted from neighboring Mount Yahiko spurred the growth of copperware production in the region. Over time, this craft evolved beyond just kettle production and adopted metal carving techniques suited for more artistic crafts during the Meiji period (1868-1912). Copperware, such as teapots, vases, and artwork, look more appealing over a long stretch of time and has become essential in daily life. Furthermore, a Tsubame tsuiki flower vase was presented to Emperor Meiji in 1894.

Production Process

- 1. Hammering

The production process of this craft varies depending on the shape of the piece but the following specifically pertains to the basic process of making a kettle. Copper plate cutting, plate shaping, decorative work, and finishing are the four basic processes. First, a copper plate is cut to size and is hammered starting with the side surface. A wooden table used exclusively for this process, is what the plate is placed on to be hammered with a wooden hammer. There are varying indentations on the wooden table which are for shaping different sections of the kettle, like a rounded side or the spout. The strength and angle of hammering are decided based on the rigidity and malleability of the copper plate. This process requires plenty of skill and experience and is a true test of an artisan’s abilities.

- 2. Thinning

Next, the copper plate is hammered and thinned. The copper plate is placed on a metal L-shaped stake called a torikuchi. This tool, also called ategane, is used for a variety of techniques and purposes depending on the item being made, and is used by being inserted in an agariban or a block made from Japanese zelkova wood. The plate needs to be hammered many times to make a kettle spout which requires much perseverance and concentration.

- 3. Annealing

Through continuous hammering, the copper plate gradually hardens and needs to be softened in a furnace set to around 650°C (about 1202°F). Hammering and heating are repeated multiple times until completion.

- 4. Shaping

Any irregularities and deformations on the body are adjusted and balanced for a beautiful shape. The surface becomes shinier from repeated hammering.

- 5. Metal carving

After the piece has been shaped, the surface is decorated. Detailed designs are drawn, engraved, and carved with a tagane or chisel. Sometimes carved areas are inlaid with gold or silver using the zogan technique. These decorative methods brighten and add elegance to the simple copper kettle.

- 6. Finishing

Lastly, to finish the texture of the metal surface, the kettle is dipped into a liquid solution. For the darkening coloring method, first the piece is coated in tin, fired at 800°C (1472°F), and hammered. Then, the product is boiled in a liquid mixture of green rust and copper sulfate, which dyes the kettle to a dark purple shade. For the red-based coloring method, the piece is boiled in the liquid several hours longer until developing to a brown color. Tsubame-tsuiki Copperware is made by repeated hammering of a single piece of copper, giving it a unique beauty. As the hammering techniques are said to be the most important part of this craft, the artisans need to be experienced and highly skilled in hammering.

Facility Information

Tsubame Industrial Materials Museum

-

Address

-

Tel.+81-256-63-7666

-

ClosedMondays (open if Monday is holiday and closed the next day) and around the New Yaer

-

Business Hours9am to 4:30pm

-

Website

Tsubame-tsuiki copperware Related Artists

- You will be redirected to the artist's page on the Gallery Japan website

See list of artworks related to Tsubame-tsuiki copperware ![]()

Other Metal works

- Nambu ironware

- Takaoka copperware

- Yamagata cast iron

- Sakai cutlery

- Tokyo silverware

- Echizen cutlery

- Osaka naniwa pewterware

- Tosa cutlery

- Tsubame-tsuiki copperware

- Shinshu Forged Blades

- Banshu-miki cutlery

- Higo inlays

- Echigo-sanjo cutlery

- Echigo-yoita cutlery

- Chiba Artisan Tools

- Tokyo antimony craft

Other Crafts Made in Niigata

- Ojiya chijimi textiles

- Shiozawa tsumugi silk

- Hon-shiozawa silk

- Ojiya tsumugi silk

- Niigata lacquerware

- Kamo traditional chest

- Murakami carved lacquerware

- Tsubame-tsuiki copperware

- Echigo-sanjo cutlery

- Tokamachi traditional resist-dyed textiles

- Nagaoka Buddhist altar

- Tokamachi akashi chijimi textiles

- Echigo-yoita cutlery

- Sanjo Buddhist altar

- Niigata-shirone Buddhist altar

- Sado Mumyoi Ware